I grew up on an island in the Detroit River in the Great Lake region of the United States. Every fall the Episcopal Church held a dinner the evening before the hunting season opened, where the priest would pray for safety and success. Hunting was normal and had direct ties to religion.

Until I moved to California I’d never encountered anti-hunters. Responding to anti-rhetoric, I began researching what prominent psychologists have said about hunting. Erich Fromm, one of the most-respected psychologists of the twentieth century, said in The Anatomy of Human Destructiveness,: “In the act of hunting, a man becomes, however briefly, part of nature again… hunting is not conducive to destructiveness and cruelty.” It is worth noting that neither any prominent psychologist nor the American Psychological Association disagrees with Fromm.

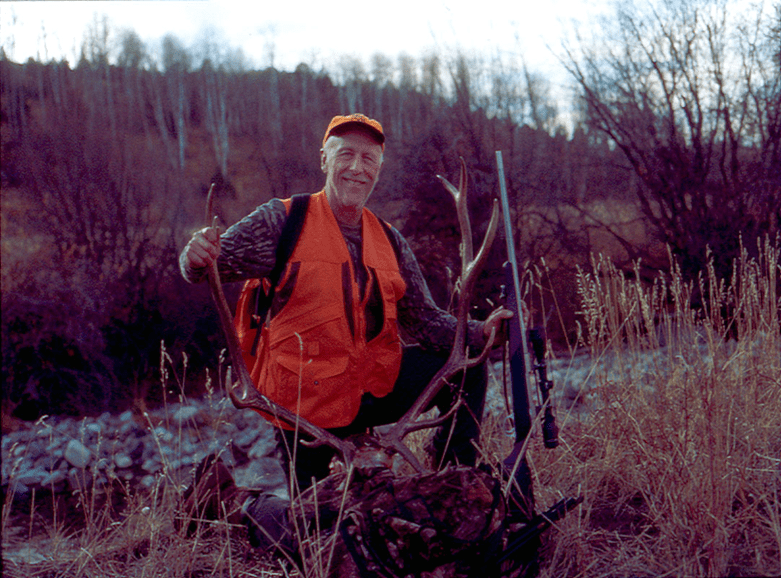

I then began interviewing people, asking what hunting meant to them. Two Christian priests told me that they had felt the presence of God strongest in their lives in two situations. One was the birth of their first child. The second was when they killed their first deer. That caused me to study hunting and religion.

For thousands of years, hunters have been guided by rituals. One US place where we can see this is Grimes Point, east of Fallon, Nevada. This is a “hunting increase site” where hundreds of petroglyphs have been made by hunters for at least 6,000 years.

Looking world-wide, most all traditional cultures conduct ceremonies to honor animals and spirits associated with hunting. Some examples: In the Yoruba religion of West Africa, the guardian spirits of the hunt are: Ogun, who presides over fire, metal working, hunting and war; and Oshosi, who presides over tracking and archery. In Scandinavia, Saami hunters recognize Alder Man as their guardian hunting spirit. Norwegians recognize Ullr as their god of hunting and archery. Finns pray to the forest spirit, Tapio, before a hunt. Greek hunters’ gods are Artemis and Acteon. The Celtic hunter’s deity is Cernunnos.

The only major modern religion that categorically doesn’t support hunting or eating meat is Jainism. Jain dietary codes say to only eat fruits and vegetables and stay away from underground vegetables like carrots and garlic.

Otherwise: there’s a Muslim Code of Conduct for ethical hunting that advises Muslim hunters to silently say a prayer before shooting an animal.

Certain casts of Hindus also don’t eat meat, however 70% of East Indians include some meat in their diet, and some Hindus practice animal sacrifice. The Hindu hunter’s god is Bhadra.

There are many different Buddhist sects. The First Precept prohibits Buddhists from killing people or animals, but they can eat meat. In Mongolia many Buddhists hunt for food, clothing and sport. There is a great film about an American, Eddie Brochin, who travels to Mongolia to learn to hunt with eagles.

About five million Asians are Taoists. Taoist monks sometimes eat vegan during fasting days, but wild animals, especially deer, are valued as their meat has more life force, “chi.”

About 80% of Japanese practice Shintoism, “the way of the Kami” or spirits, one of which is Hoorai, the god of hunting.

The Torah says Jewish people should eat only “kosher” animals that have both split hooves, and chew its cud — cows, sheep, goats and deer. Kosher birds include chickens, ducks, geese, turkeys and pigeons. No problems with hunting kosher animals.

Christianity is the most popular religion in the world with 2.1 billion followers, nearly 240 million in America. In Genesis 1:28-30 the Bible says that God blessed man and said to them, “Rule over the fish in the sea and the birds in the sky and over every living creature that moves on the ground.” Christians in general have no taboos against hunting, however some denominations such as Trappists, Benedictines, Cistercians, Rosicrucians, and Seventh-day Adventists, choose a vegetarian diet.

Quakers generally agree that men have a right to take the lives of animals, wild or tame, for their food, and to keep away predators like coyotes that consume livestock.

An Expert Opinion

One expert on hunting is Catholic priest and Chairman of the Philosophy Department at St. Louis University, Father Theodore Vitali, who’s also an avid hunter and ethicist for the Boone and Crockett Club.

One expert on hunting is Catholic priest and Chairman of the Philosophy Department at St. Louis University, Father Theodore Vitali, who’s also an avid hunter and ethicist for the Boone and Crockett Club.

Father Vitali says: “For a hunter to be ethical, he needs to have a reason to kill—the two most prominent reasons being the right to obtain healthy food, and secondly, the conservation value for wildlife management. A third would be self-defense. A fourth would be management and conservation of the land, such as controlling deer in urban areas, lessening crop damage, or preventing zoonotic disease.”

Father Vitali says that Fair Chase is the ethical, sportsmanlike, and lawful pursuit and taking of free-ranging wild game animals that “puts you on equal terms with the animal.”

Father Vitali describes an incident in Ontario in 1987 that occurred while hunting bears where hunting changed his life. He says: “About midway through the hunt I was in a blind along a deserted logging road deep in a typical northern Ontario forest. It was dark and foggy, and at times raining. It was about 8 pm. The bait I was hunting over was about 30 yards away. I sat in my blind, hunkered down under my rain gear and poncho, resting my rifle under the poncho. Suddenly, I sensed something behind me. I knew that a bear might circle a hunter and come to the bait from behind him. Therefore, I slipped the safety off of my rifle and very slowly turned around to see what was there. About seven or eight paces from me sauntered a large male wolf. My eyes caught his as I watched him pass by me, climb a small embankment, eye the bait, pause for what seemed a very long time, then he turned and drifted off into the darkness of the forest. I felt no fear at all. I felt entranced by his presence. I didn’t want him to go away. I felt as though this was some kind of communion, something much more than the ordinary in that moment. I was changed forever by and through this experience. I received the gift of knowing who and what I was and am and thus who and what I am before God.”

Christian hunters have a patron saint, St. Hubert. He was born in 638 AD in Belgium. He became a prince and enjoyed the “good life” of nobility, but most of all he loved hunting. One Good Friday, when he should have been in church, Hubert galloped off to hunt stag. His hounds cornered a large stag. As Hubert approached the stag, suddenly Hubert had a vision of a crucifix appearing over the stag’s head. A voice spoke to him: “Hubert, unless thou turnest to the Lord, and leadest a holy life, thou shalt quickly go to hell.” Hubert climbed down off his horse and begged forgiveness. The voice instructed him to seek guidance from the Bishop of Maastrichcht. Not long after this, Hubert’s wife died in childbirth. Hubert soon became a priest.

Saint Hubert

Hubert became a Bishop and established Christianity in large sections of the Ardennes Forest. Ultimately he became the saint of hunting and butchering. Many celebrations of St. Hubert are held on November 3.

Hubert became a Bishop and established Christianity in large sections of the Ardennes Forest. Ultimately he became the saint of hunting and butchering. Many celebrations of St. Hubert are held on November 3.

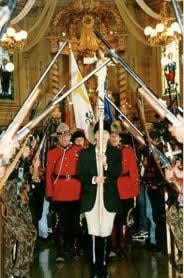

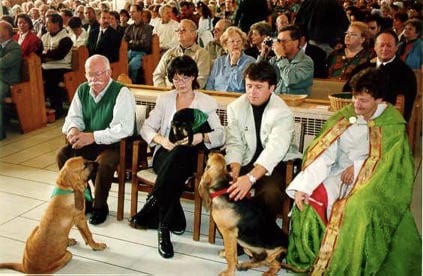

In St. Ignace, Quebec, a mass of St. Hubert is celebrated with the sound of horns as armed hunters and their dogs enter the church for blessing. In the church, hunters raise their guns over the heads of the procession, which includes clergy and mounted police.

Some Way Religion Guides the Hunter — Prayers to Start the Hunt

Photos of the St. Hubert’s Day celebration in Quebec are courtesy of Patrick Plante.

Many hunters say prayers before they begin to hunt. In northern Scandinavia, Saami, the indigenous people of that area, leave an offering to Alder Man, their hunting spirit, and make prayers at special rocks call “seida,”

Taking the Shot

My father taught me that when considering shooting at a game animal I should pray to myself, “God, if I take this shot, please let me kill quickly and cleanly and recover the animal I have shot. Otherwise let me miss cleanly.”

Jim Posewitz, author of Beyond Fair Chase, told me that: “If there is a sacred moment in the ethical pursuit of game, it is the moment you release the arrow or touch off the fatal shot.”

Giving Thanks and Blessing the Hunters

Film and television actor Marshall Teague says a prayer when he kills an animal: Lord, bless this noble creature that has given his time and spirit to engage in the chase. Permit him green pastures to graze, thick forests to roam and take his heart and soul into his blessed hands.

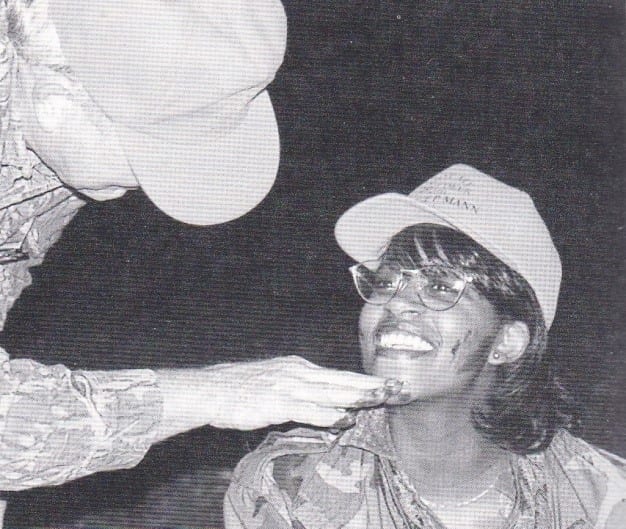

Scottish hunting guide Michael Roberts relates that in Europe some hunting guides conduct blooding rites by painting the cross of Saint Hubert in blood on the hunter’s face.

“Blooding” is performed world-wide. In the 1989 docu-drama film, “In the Blood,” which retraces Teddy Roosevelt’s 1909 African safari, professional guide Robin Hurt performs a blooding ceremony on Tyssen Butler, who has taken his first big game animal, a cape buffalo, using Roosevelt’s rifle.

George P. Mann took his first deer when he was in his teens and his guide painted his face with the deer’s blood. It changed his life. As George grew older, his love for hunting grew. Around his home in West Alabama there were no deer, so George initiated a stocking program to bring deer into Lee County. Mann then set aside a tract of several hundred acres of his personal land for people to take their first deer. For each, George conducts the blooding ceremony.

Another honoring of game and hunter is “the last bite,” “letzebissen” or “letzer bissen” in Austria, Holland and Germany. Germans break (never cut) a twig from one of five tree species: oak, pine, spruce, fir and alder. With the animal placed on its right side upon a bed of leaves as a sign of respect, they pull the broken twig through its mouth from one side to the other and leave it clamped between its jaws. Another sprig of greenery is placed in the successful hunter’s hatband. If you hunt in Germany or Austria, you will hear the term “Weidmannsheil,” which means congratulations and good luck.

Also in Europe, at the end of the day, all animals taken are laid out on the ground and hunters and guides stand beside the animals while a guide blows a hunting horn, and prayers are said honoring the animals.

The bottom line is that opposition to hunting is based on opinions, not science or religion. World-wide hunting is a spiritual act and a way to develop strong conservation attitudes.

The bottom line is that opposition to hunting is based on opinions, not science or religion. World-wide hunting is a spiritual act and a way to develop strong conservation attitudes.

You can comment on this article or ask James questions here.